THE SWIPE RESEARCH PROJECT PROPOSES TO CONSIDER THE METHOD OF GESTURAL TEXT ENTRY AS A WRITING SYSTEM IN ITS OWN RIGHT. 📄

THE COPYBOOK DESIGNED TO LEARN THIS WRITING SYSTEM CAN BE PRINTED FROM THIS WEBPAGE USING CHROME BROWSER. 🖨

Swipe, writing copybook

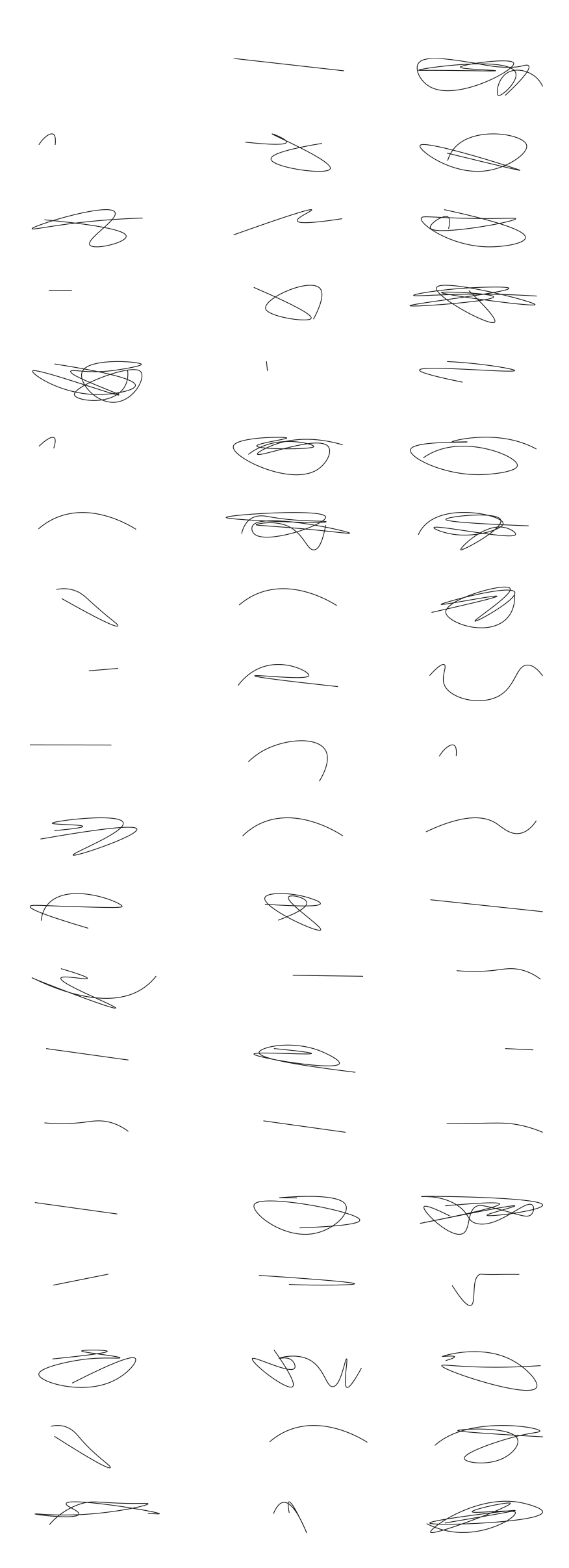

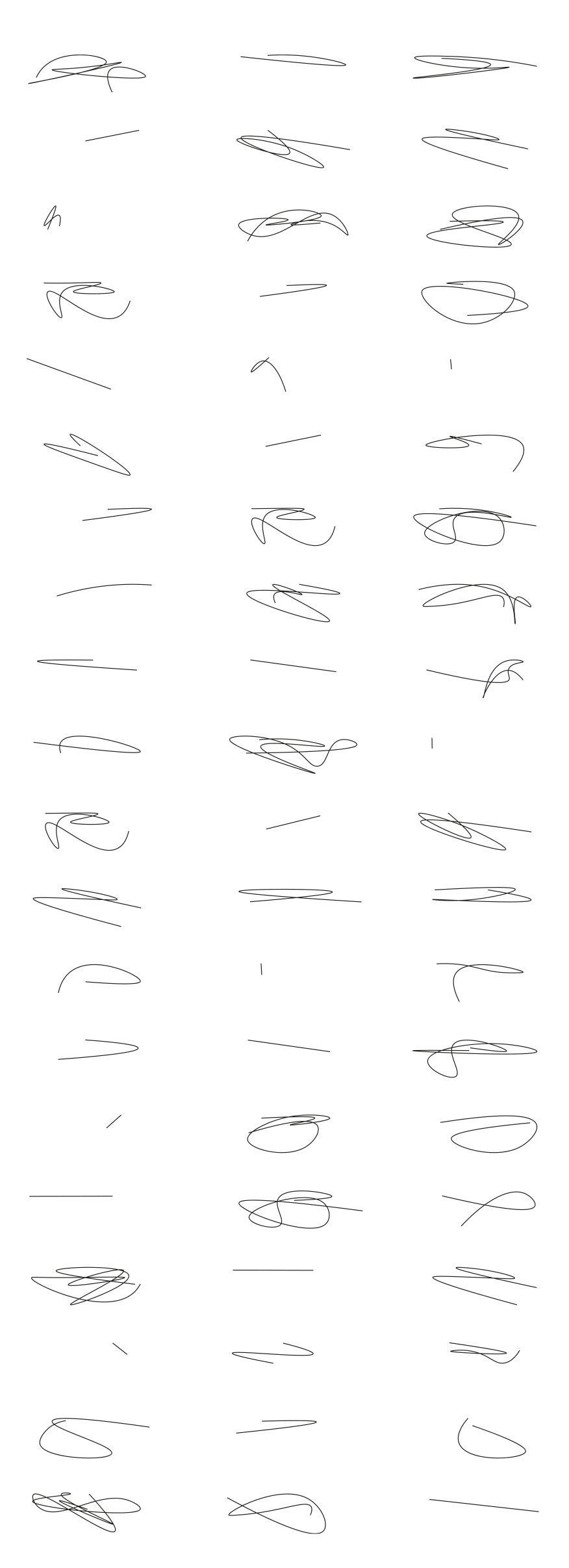

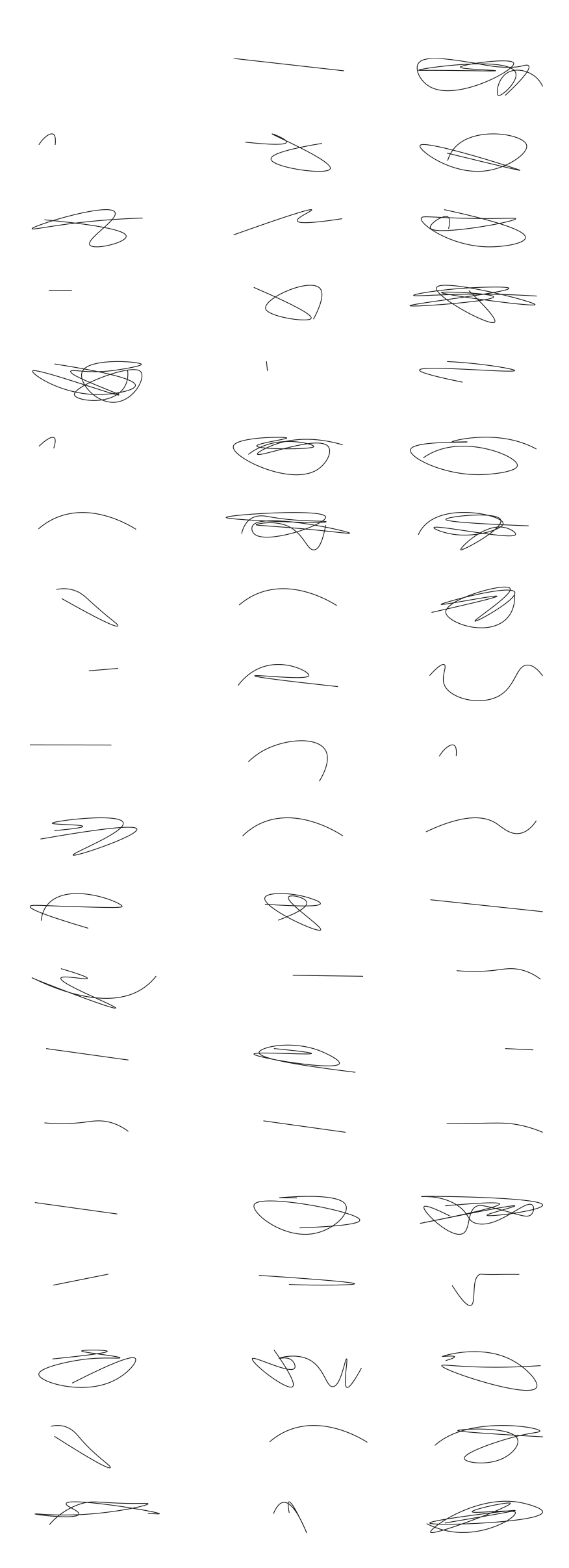

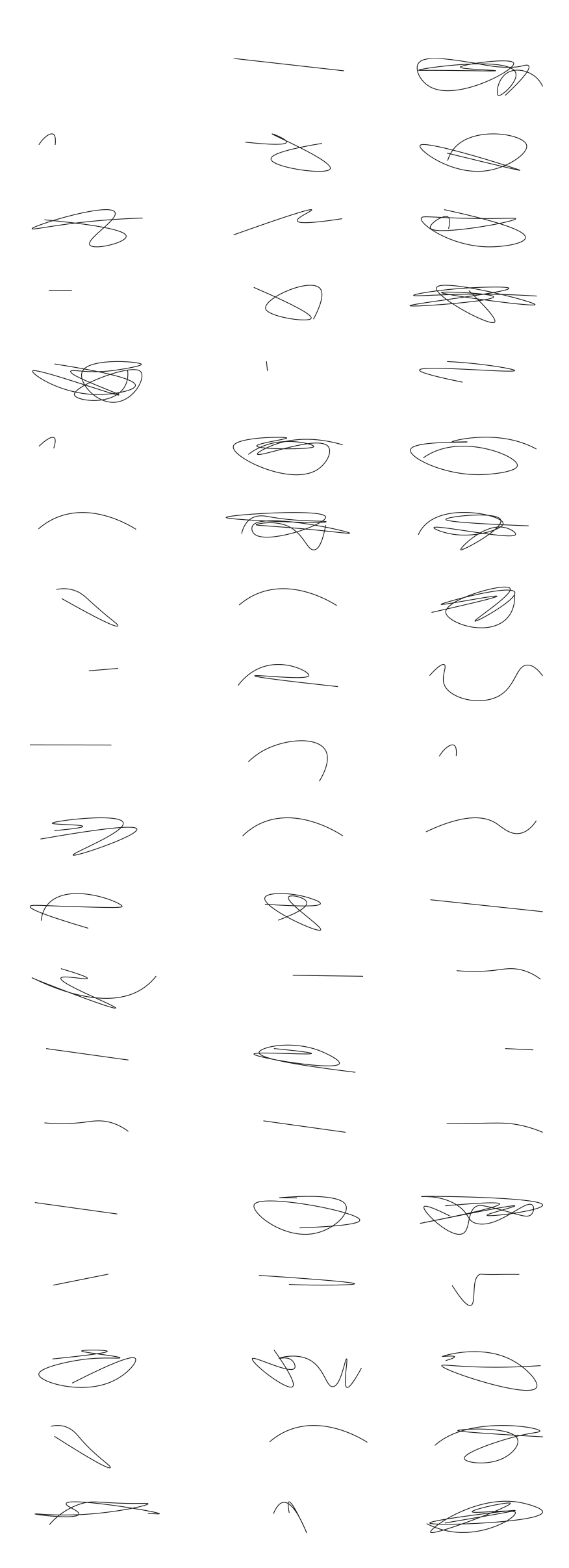

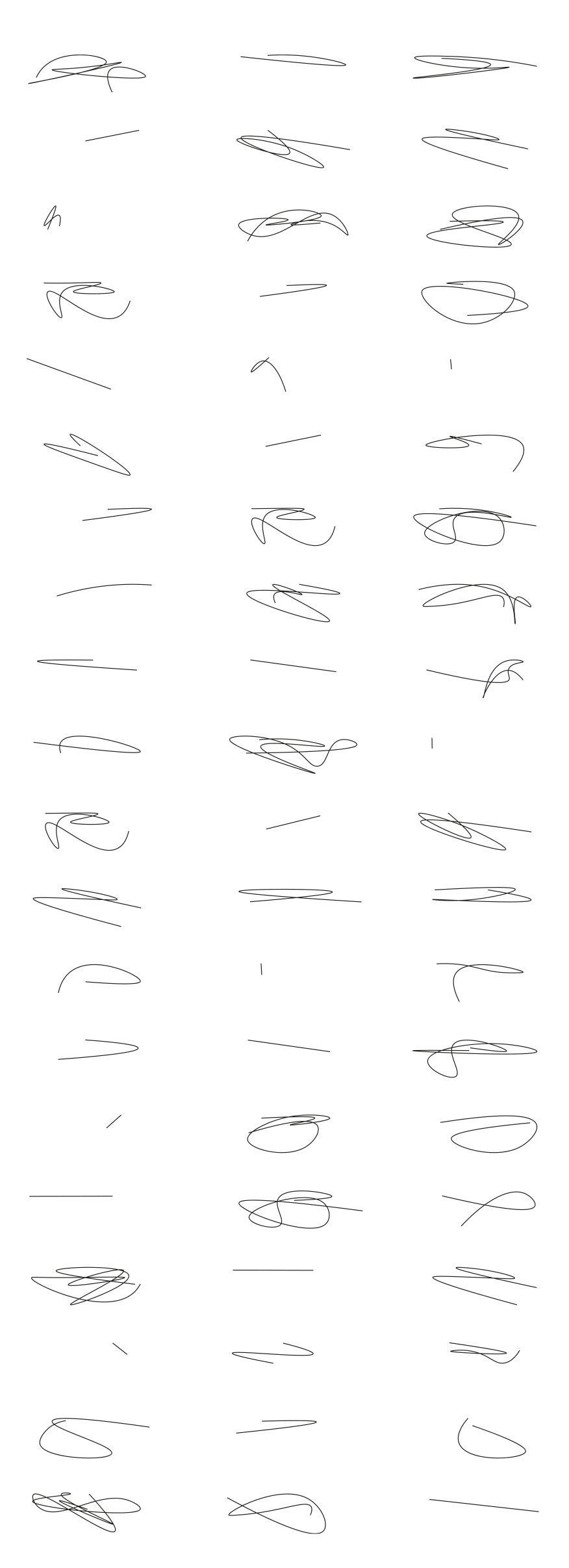

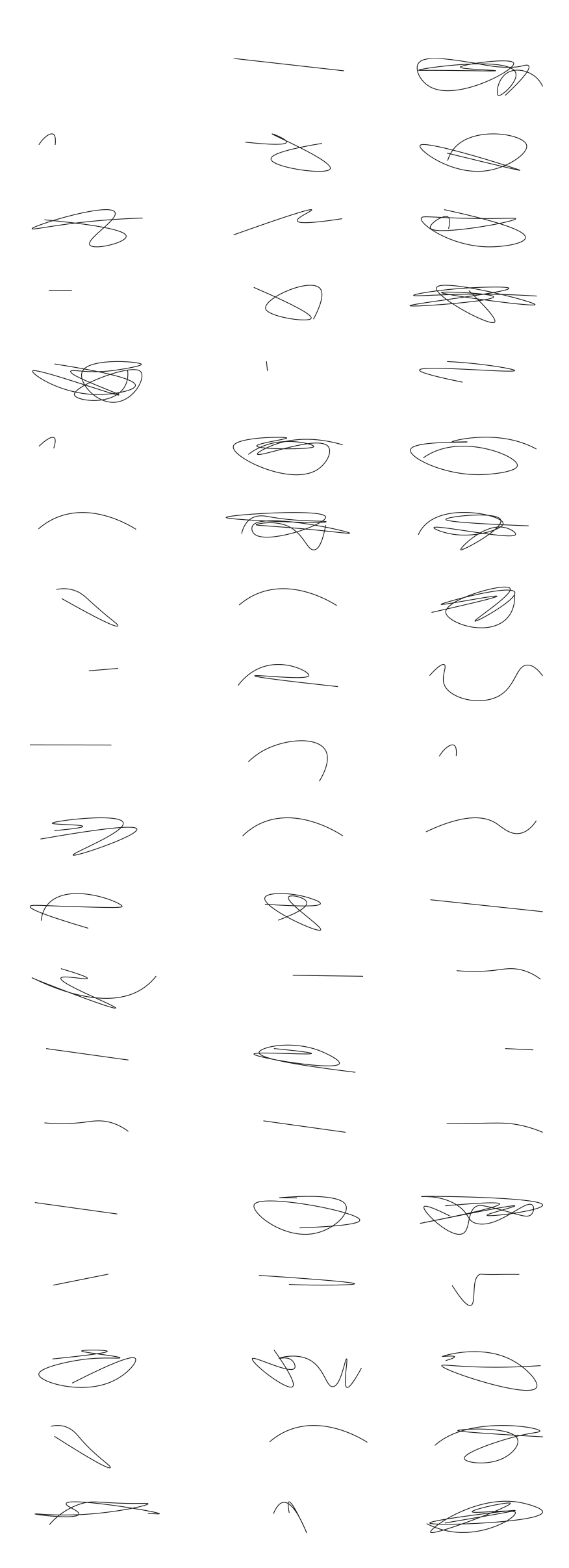

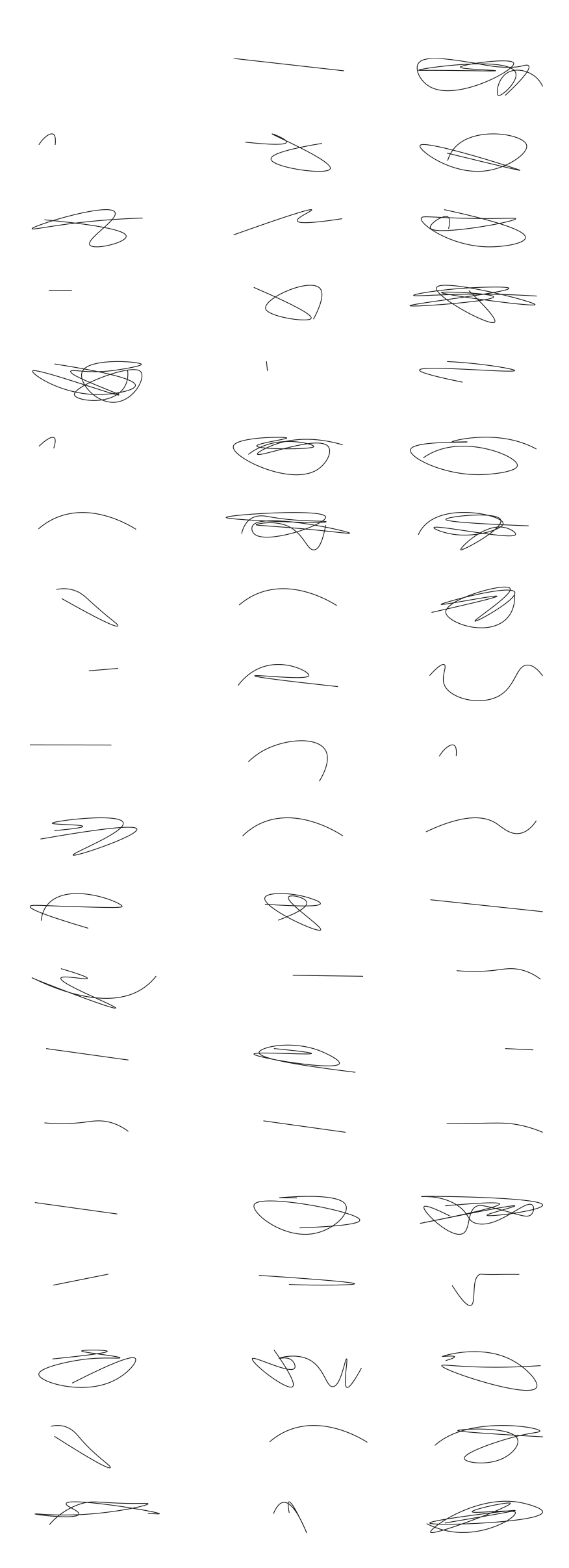

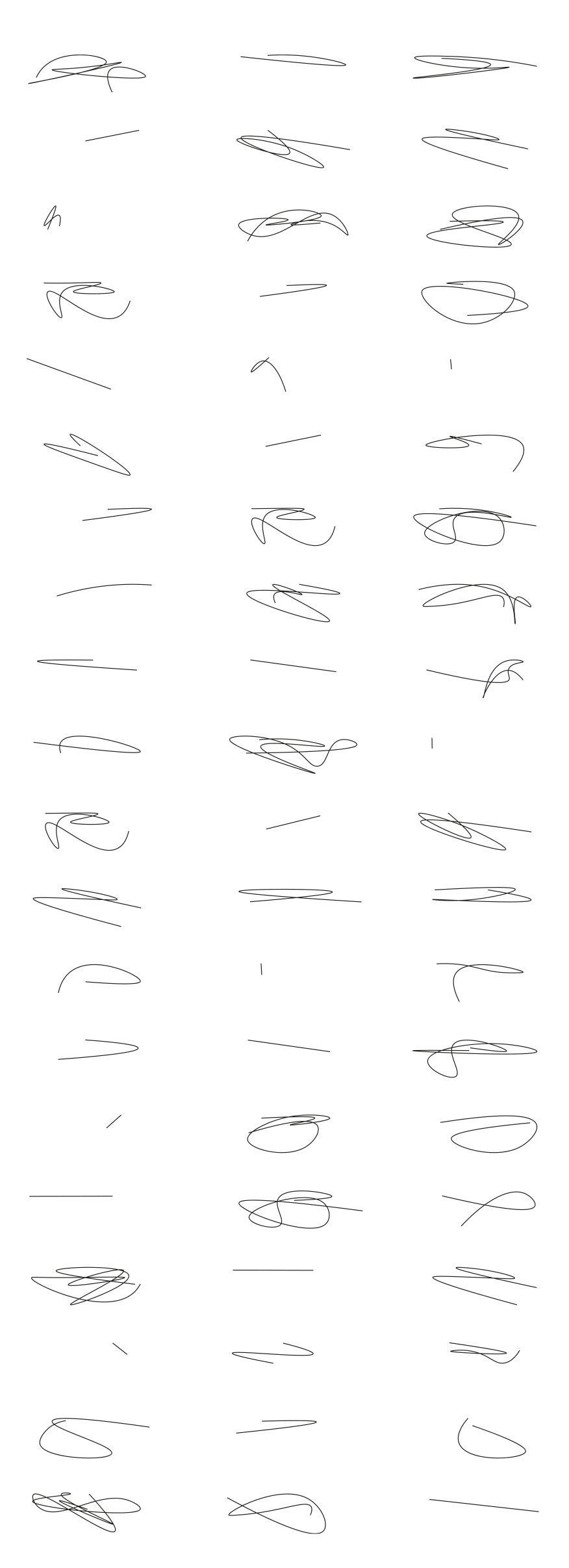

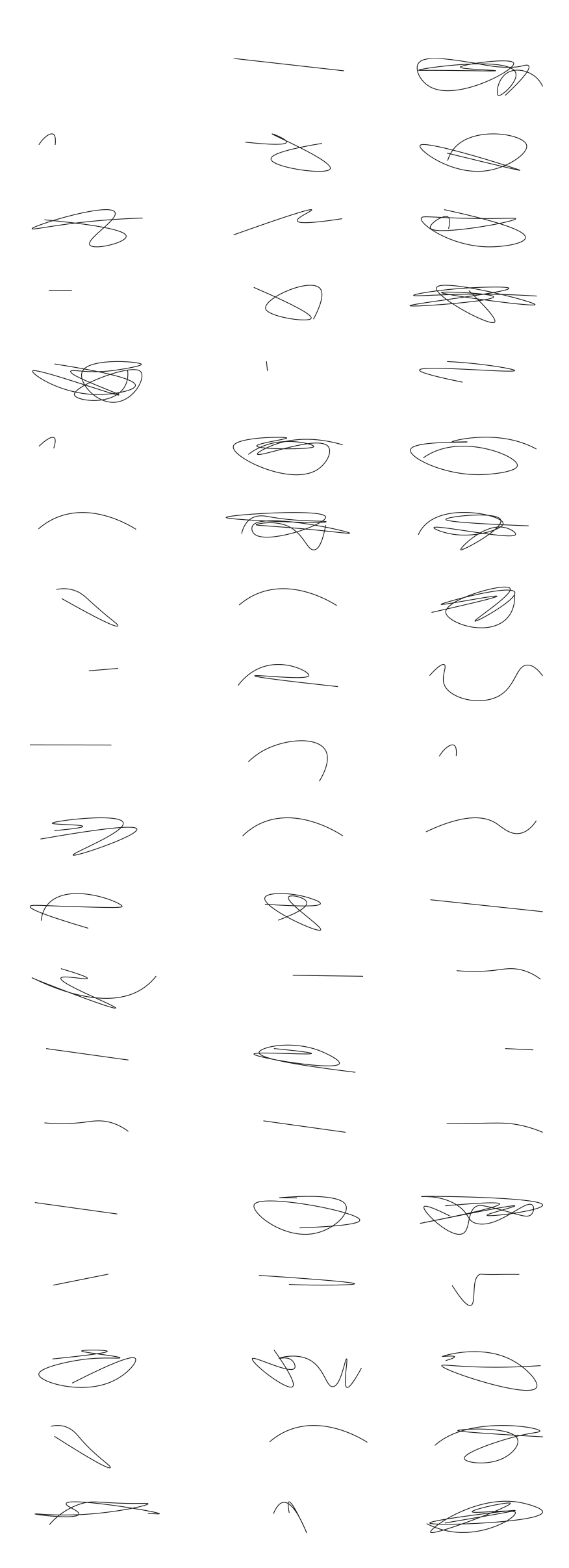

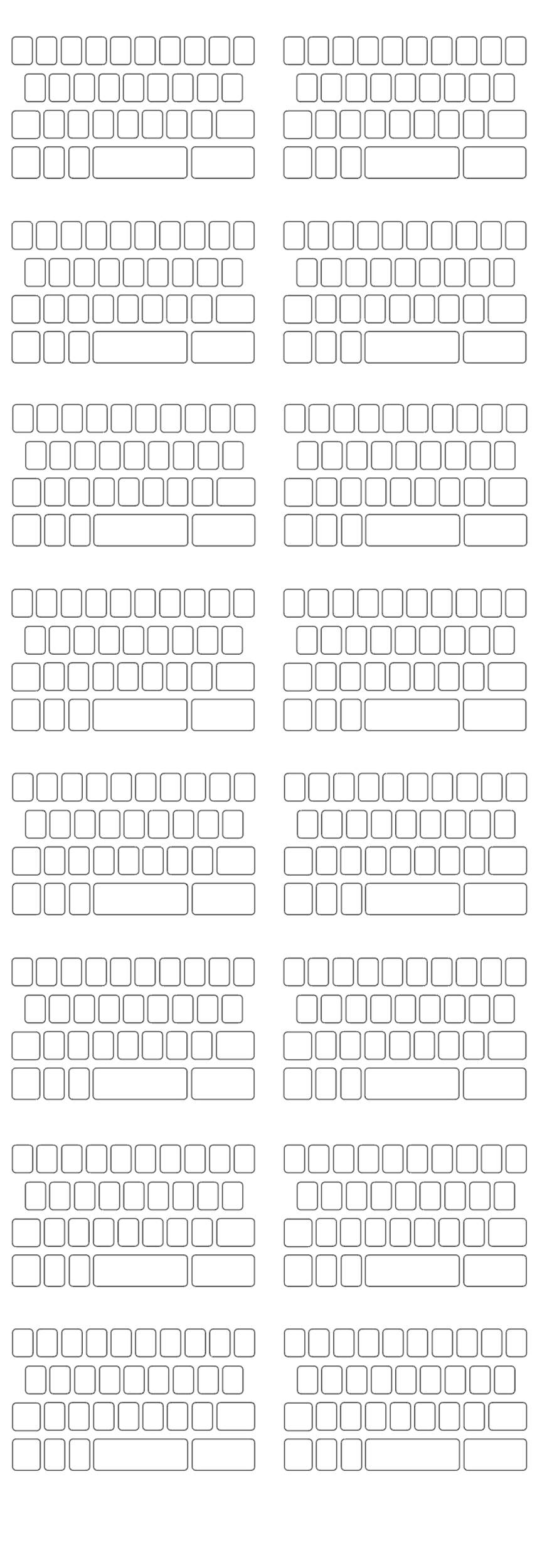

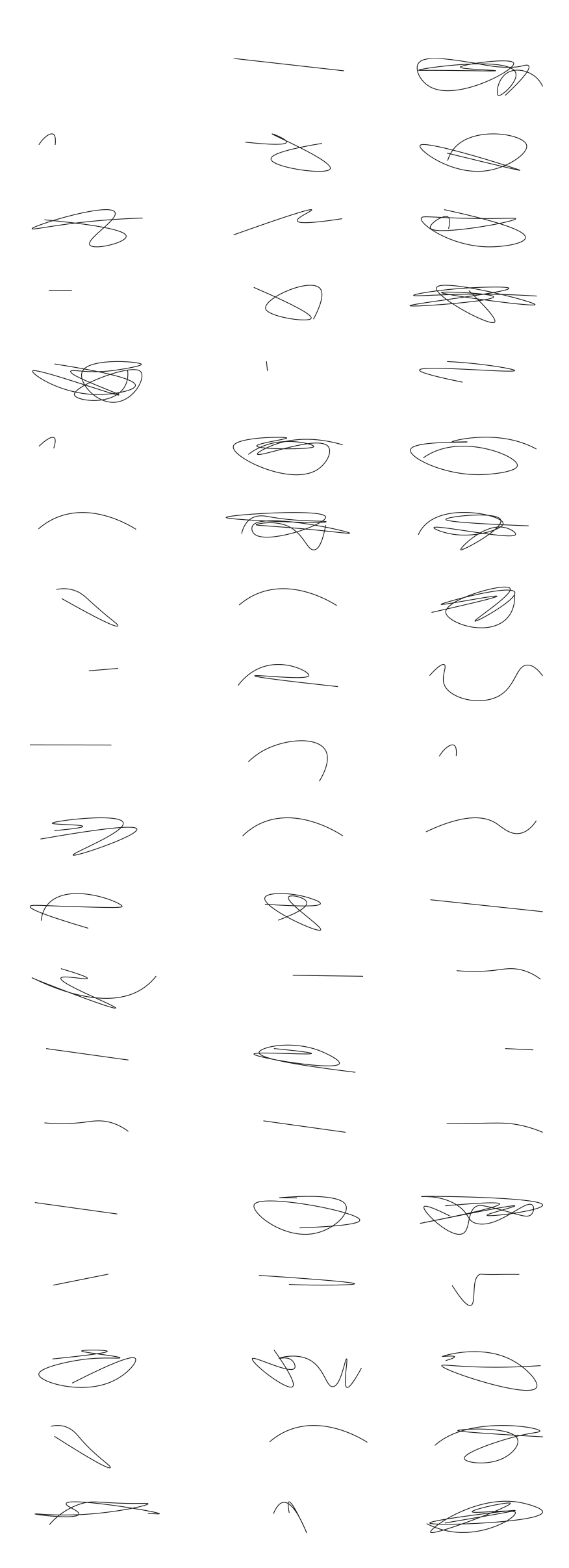

"Swipe" has become the established term to refer to the set of operations on digital devices involving sliding a finger across the surface of a touch screen. Sliding to open, scratching to erase, or moving right to accept are all actions resulting from the mutation from mechanical keys to touchpoints and finger choreographies. Typing text has not been exempted from such a mutation. Indeed, gestural text entry keyboards, more widely known by their commercial names Swype or Swiftkey, allow writing by sliding a finger from the first to the last letter of a word on a screen keyboard. The artwork Swipe, by Bérénice Serra, records these tactile choreographies to raise the gestural text entry method into more than a tool, namely into a writing system in itself. The movements thus become monograms. This writing copybook proposes practical and poetic exercises in order to learn this system, outside of its digital environment, as a way to remodel cursive writing. The essay "Swipe ou l'écriture tout court" written by Bérénice Serra and Gianni Gastaldi, at the end of the notebook, was published in the journal Formules, on the occasion of the 22nd issue directed by Lucile Haute and Allan Deneuville.

Bérénice Serra

Born in 1990, Bérénice Serra is an artist and researcher based in Caen (FR) and Zürich (CH). She teaches publishing and digital practices at the École supérieure d'arts & media de Caen/Cherbourg, in Normandy. Her practice, both visual and theoretical, focuses on the notion of publication in the digital age.

Design and development: Bérénice Serra

Texts: Bérénice Serra & Gianni Gastaldi

Date: juillet 2020

URL: berenice-serra.com/swipe

Last update: october 2021

Acknowledgements: Allan Deneuville, Lucile Haute, Lorène Ceccon and Isabelle Daëron

Translation : Barbara Sirieix

40

![]()

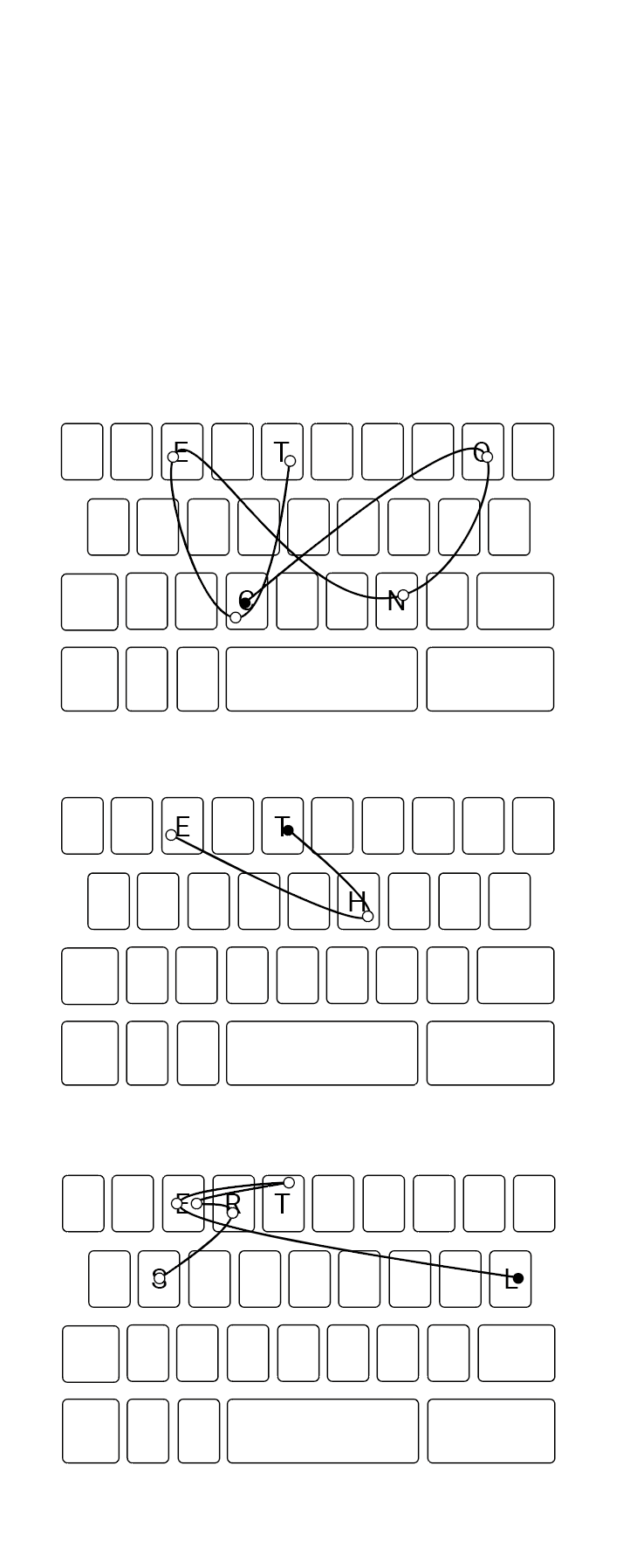

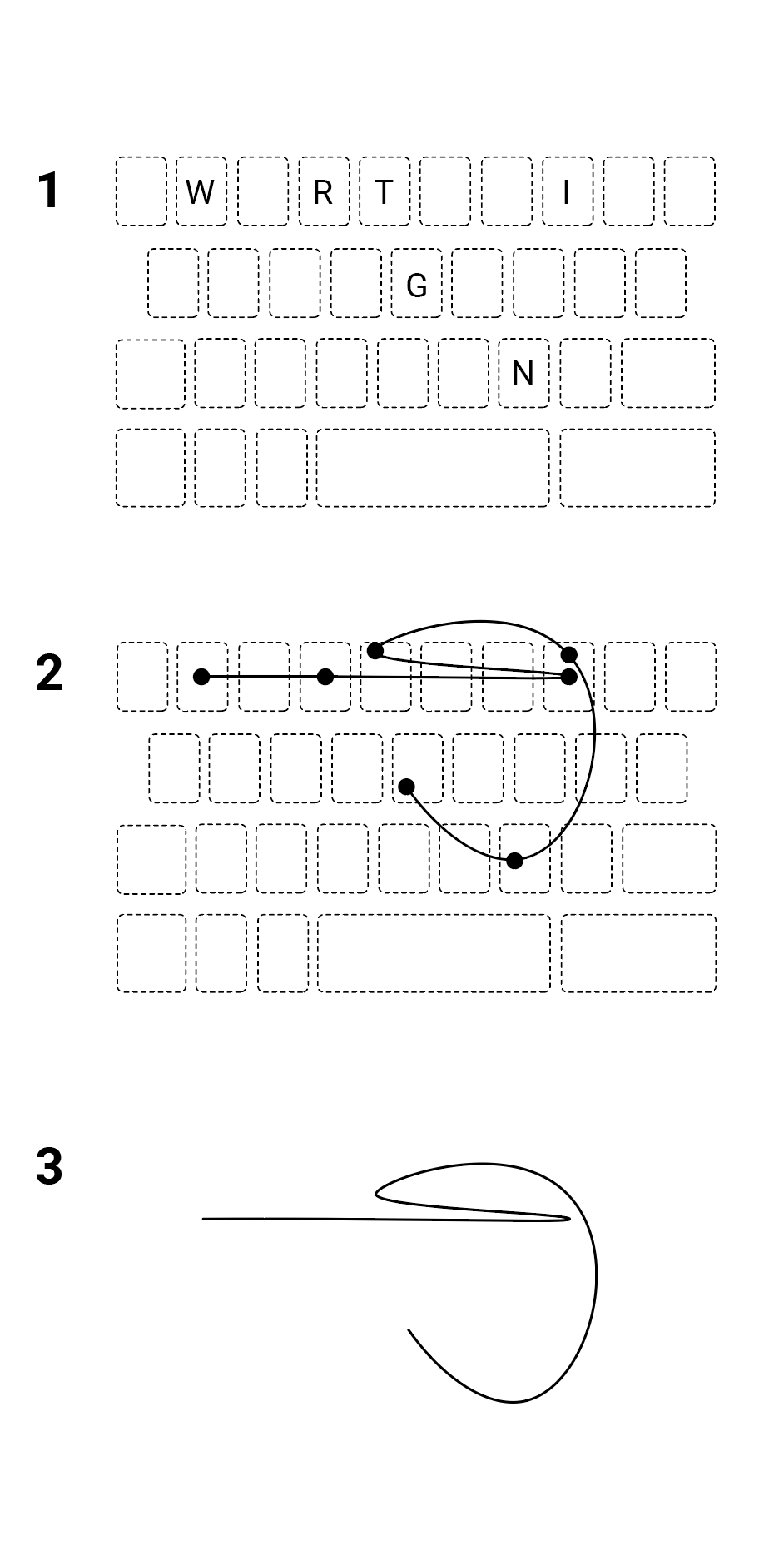

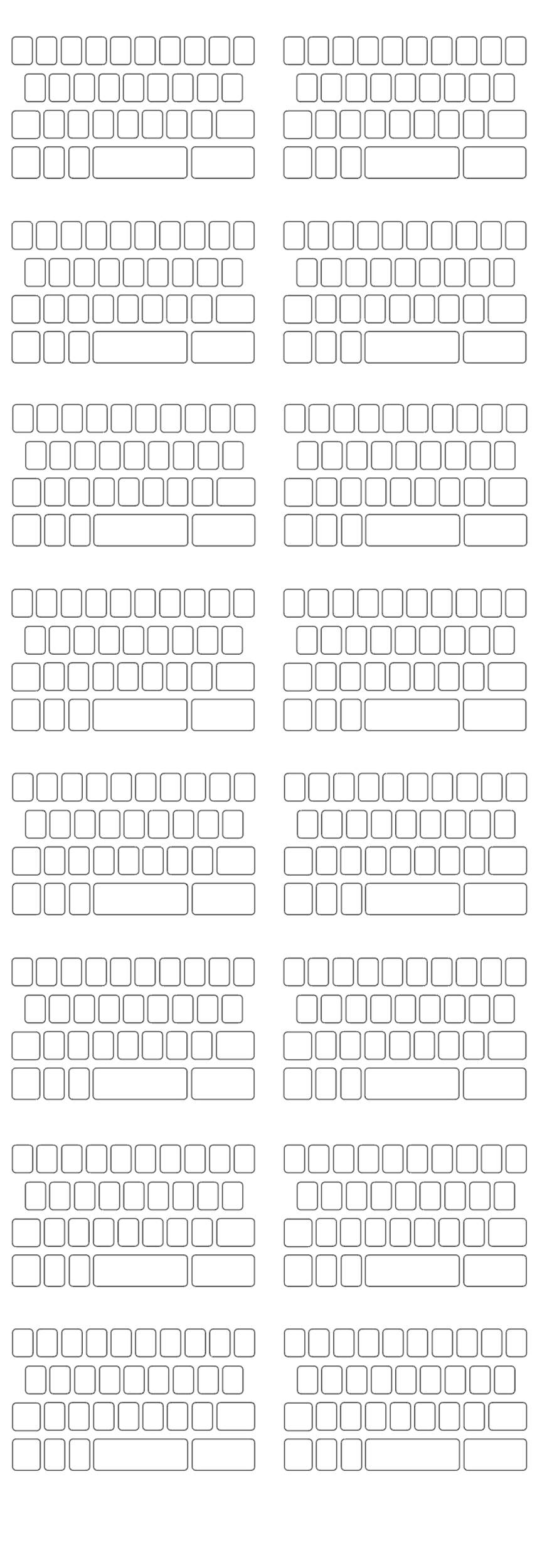

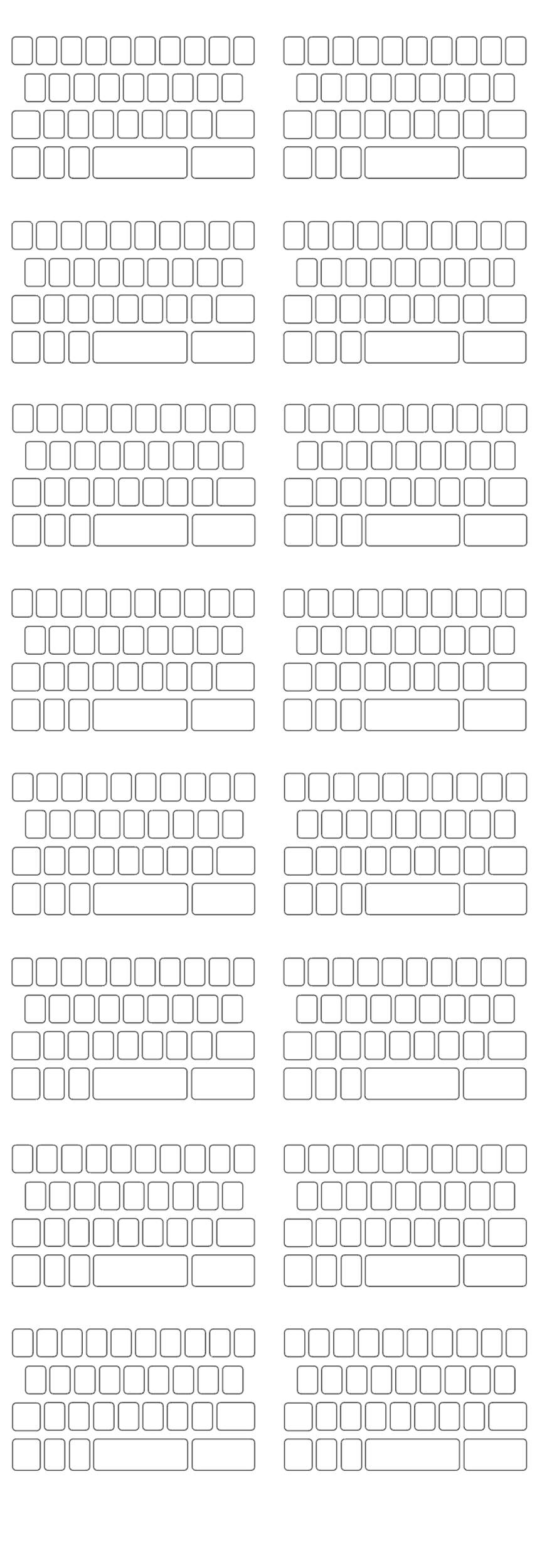

Part A. three principles of swipe writing

Notes

[1] The fact that we call this computer "telephone" is just an anecdotical fact.

[2] It is assumed that more than 45% of the world population is using a smartphone in 2021 (source: Newzoo, ID 330695).

[3] UA description of the origins of their work can be found in Kristensson’s website: http://pokristensson.com/gesturekeyboard.html.

[4] About 40 words per minute instead of 30 (Palin et al., 2019; Reyal et al.,).

[5] The artwork Swipe was presented at Shadok-Fabrique du numérique (Strasbourg, 2019) as well as at Ars Electronica festival (Linz, 2019) For more details about the work, see bereniceserra.com.

[6] Hjelmslev, Louis. Prolégomènes à une théorie du langage. Paris : Minuit, 1971, § 12.

[7] For instance, the word inevitable produces on a computer keyboard something like "ijnhgredfvbhuiuytrezazerfvbnjklkjhgre".

[8] Saussure (de), Ferdinand. Cours de linguistique générale. Paris : Payot, 1916, p. 165.

[9] Ducrot, Oswald ; Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. Nouveau dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences du langage. Paris : Seuil, 1999, p. 23-41.

References

Ducrot, Oswald ; Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. Nouveau dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences du langage. Paris: Seuil, 1999.

Foucault, Michel. "La Peinture Photogénique". Dits et écrits. Paris: Gallimard, 2001, pp. 1575-1583.

Hjelmslev, Louis. Prolégomènes à une théorie du langage. Paris: Minuit, 1971.

Palin, Kseniia ; Feit, Anna Maria ; Kim, Sunjun ; Kristensson, Par Ola ; Oulasvirta, Antti. "How Do People Type on Mobile Devices? Observations from a Study with 37,000 Volunteers", Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services. Taipei: Association for Computing Machinery, 2019.

Reyal, Shyam ; Zhai, Shumi ; Kristensson, Per Ola. "Performance and User Experience of Touchscreen and Gesture Keyboards in Lab Setting and in the Wild". Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Séoul: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015.

Saussure (de), Ferdinand. Cours de linguistique générale. Paris : Payot, 1916.

Zhai, Shumi ; Kristensson, Per Ola. "Shorthand Writing on Stylus Keyboard". Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Lauderdale: Association for Computing Machinery, 2003.

36

From this perspective, what we call "digital" appears only as the successful

wager on the performative dimension within text itself, forcing the traditional

forms of textuality

to become nothing more than the surface of this new textuality,

whose performative depth is constantly ready

to be revived.

Hence this constant tension found within digital practices, between the internal

performative dimension of textuality (codes and programs) and that emanating from

human expression which, although on the surface, still governs

the evolution of the

writing of natural languages. A tension whose resolution has been invariably sought

through an anthropomorphization of the machine, of which the notion of "intelligence"

is today the most presumptuous, if not the most revolting of the expressions.

The perspectives on the textuality of our time that a practice of digital writing like Swipe's

can offer could therefore provide precious leads against the atavistic fascination to make computers speak.

It could remind us that computers already have their own language, which does not need to ape ours to be

subject to the same principles. And which perhaps lacks nothing to be natural either. It could also remind

us that a poetry of its own is

to be sought, there, outside of any caricature, like here, somewhere other

than in the words. And remind us also that the key to this alliance resides, perhaps, in bringing together

all these digital experiences of the textuality with that, if not immediate, at least spontaneous experience

of writing in natural language. In other words, in writing tout court.

34

In the limit, one could imagine an initial vocabulary made up only of elementary gestures for irreducible units (letters for example), and let this vocabulary grow dynamically according to the frequency of combinations of these units in the users’ practice. Given the different levels of articulation through which this principle operates, this process would make this writing system directly sensitive not only to lexical but also grammatical and stylistic transformations in the language. All these aspects point to one last essential property of language revealed by Swipe. If gesture keyboard entry can be seen as a writing system in its own right, this means above all that it is capable of becoming the expression of a natural language. But a language is not natural because it is spoken by humans. It’s natural because it is performed and by being performed it changes. It is the merit of historical or comparative linguistics to have understood this fundamental property at the turn of the 19th century and to have made it a constitutive principle of natural languages: a language is a tool of communication; and like any tool it wears out, leading to changes in the whole system, thus becoming a record of cultural traces. However, the perspective of historical linguistics on this change is, if not negative, at least pessimistic: usage only affects the language system by eroding it. Therefore, the history of languages is only that of their decline. It was not until Saussure that this change was understood as the source of a creative power, manifested in the fact that mechanisms of resystematization are at work at each point in the evolution of a language [9]. These mechanisms are precisely what gesture keyboards have to offer to a new writing system. Unlike typewriting, the practice of gesture keyboard entry does not only lead to an increase in speed – a purely technical and quantitative improvement. The performance of a system like Swipe offers a specific openness that becomes creative because it is directly linked to reorganizing effects of the whole system. Think about the overall effects generated by the incorporation of a new sign into the vocabulary. The integration of a new pattern forces the whole system to redefine the margin of possible variation for all the figures which occupied until then the space of the newcomer. A wholly new aesthetic is implied in these shifting processes and, at the crossroads of the linguistic and the figurative, poetry of a new kind suddenly becomes possible, with mechanisms still unknown, inviting us to even more openings.

32

But this sequence does not result from the identification of breakpoints in these paths either, since the

absence of solution for a continuity in the paths only improves the performance. The final identification

of a word out of the unstable multiplicity of possible paths is attained otherwise, by using the capacity

the resulting figures have to discriminate an element among a finite list of words. More precisely, a

finite list of words being given (i.e. a vocabulary), each word is mapped to its own prototypical pattern,

so that any path performed on the virtual keyboard can be associated with the closest pattern in such a domain,

and thus select the corresponding word. Therefore, the possibilities considered by the system are drastically

reduced, because the size of the vocabulary is several orders of magnitude smaller than the set of possible paths

on the screen keyboard.

This mechanism has a double advantage. On the one hand, it eliminates spelling errors, at least as they exist in a

traditional alphabetic system, since the words produced are systematically chosen from a vocabulary that contains only

linguistically correct forms. On the other, it leaves a lot of room for individual variation in the writing of words,

since a path only fails to discriminate the correct word when the resulting figure is sufficiently close to the pattern

associated with another word in the list, a situation that is all the rarer since additional means can be used to avoid

confusion (such as other words in the context). This individual variation can then open the space for a true calligraphy,

with an expressive power sorely absent in traditional typewriting.

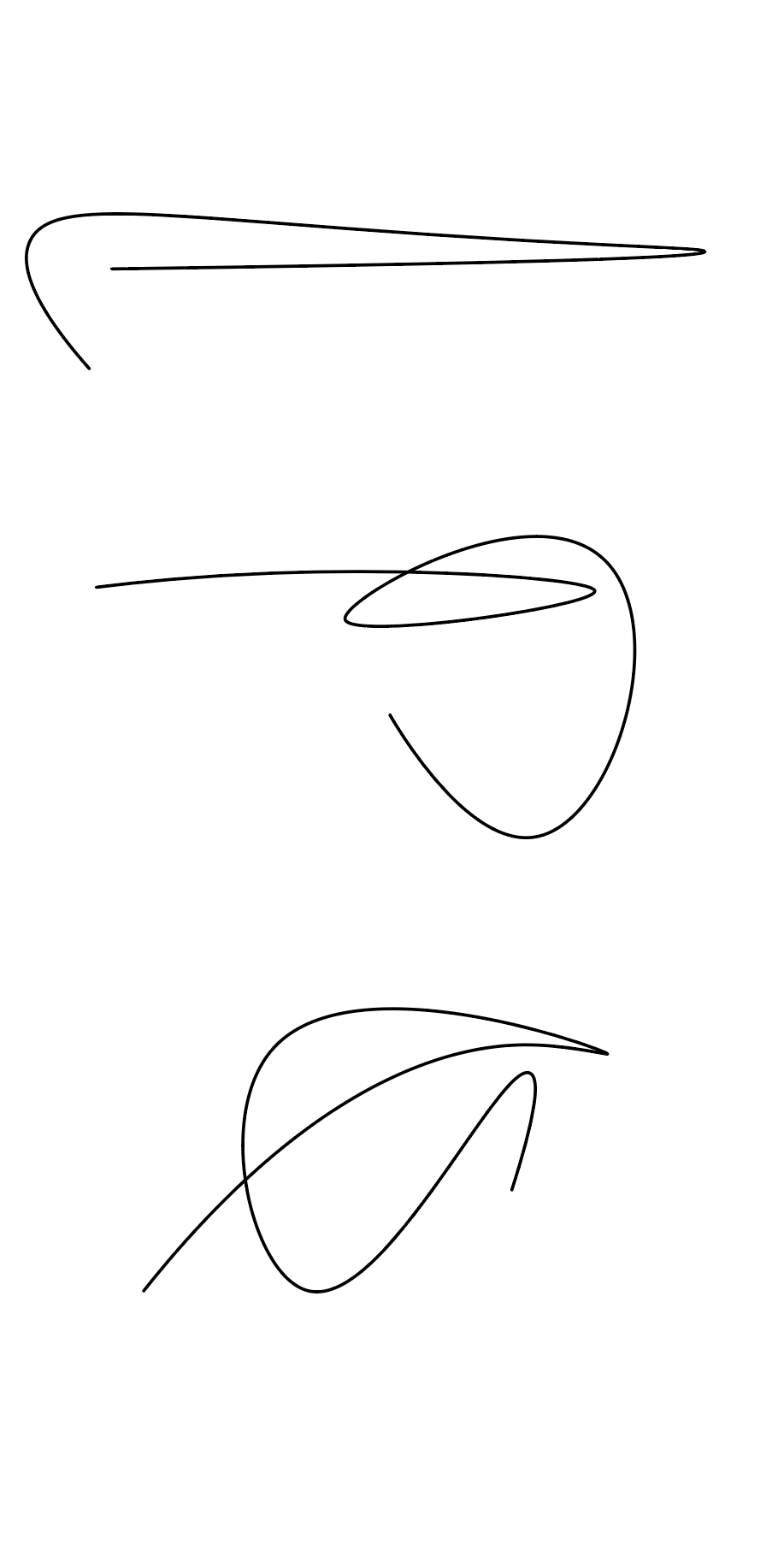

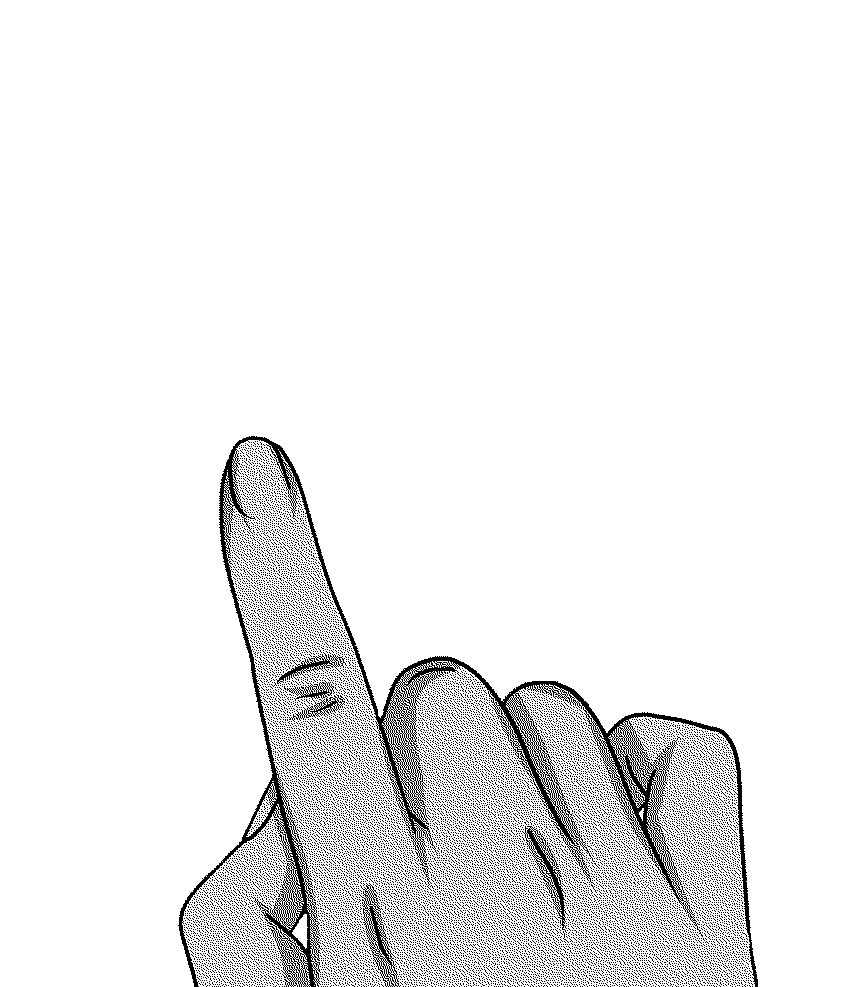

Yet, this inexorable limitation of the graphical to a finite list of possibilities, the forced passage from the continuous to

the discrete, from geometry to algebra, constitutes much more than a technical tinkering. Just like the principle of stratification,

it concerns the very essence of language. For, as Shannon showed, communicating information in a language amounts to little more

than picking a term among a finite set of unevenly distributed elements. Such a view is not unlike Saussure’s when, putting forward

a conception of linguistic units in terms of "values", he affirmed that “values in writing function only through reciprocal opposition

within a fixed system that consists of a set number of letters" [8]. Significantly, he proposed the example of three possible

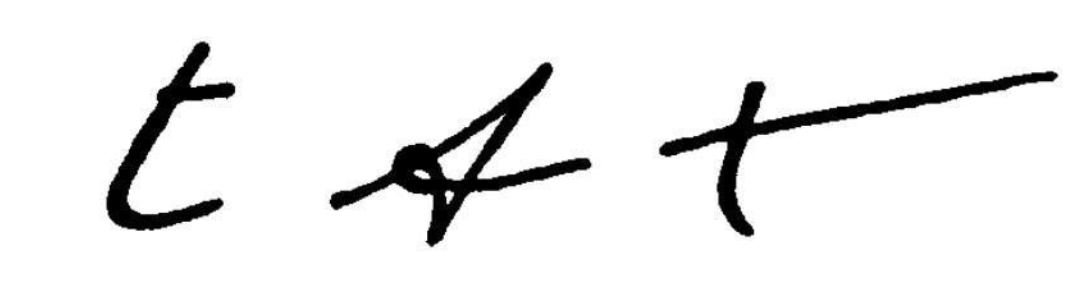

written variants of the letter t, as disparate as

possible and yet identifiable provided that they can be

distinguished from other letters such as l or d (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Variations of writing of the letter t. Saussure, 1959, p 119.

Figure 1. Variations of writing of the letter t. Saussure, 1959, p 119.

![]()

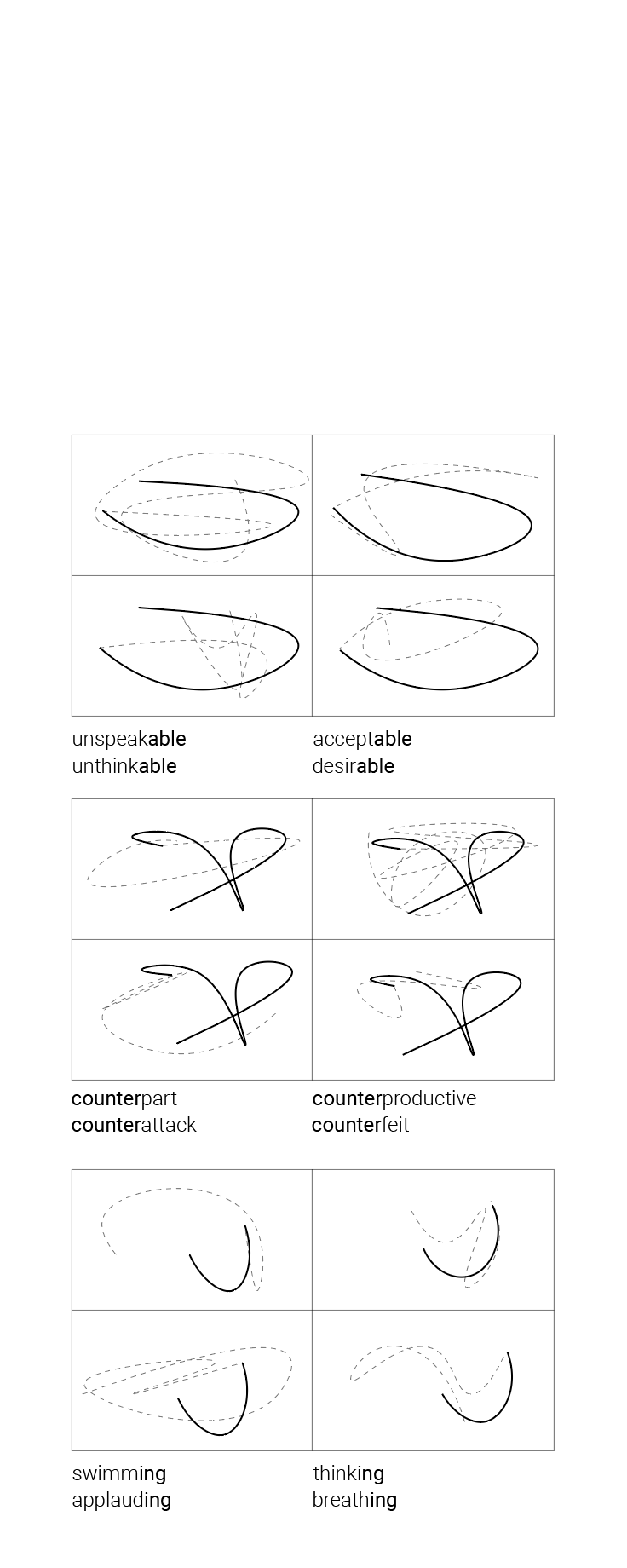

Part B. three writing exercices

30

Following an approach of structural semiology [6], the monograms should rather be conceived as figures, i.e. atomic units of expression whose reciprocal relations constitute the ground of a sign system. But, unlike usual figures (such as characters), these figures are also signs since they are necessarily tied to content.

The stratification of language

The writing system that emerges in this way is endowed with remarkable properties. Starting with the fact that alphabetic typewriting on a keyboard recovers one of the main features of cursive writing, or even of the principles governing ideographic or pictographic writing. As in the latter, grasping words as simple expressions (i.e. not composed, however complex they may be) reminds us that the units of language, insofar as they have a meaning, constitute more than an arbitrary sequence of insignificant characters. They are endowed with a formal cohesion which distinguishes them from a manifold of other combinations of the same characters which do not have the fortune to belong to a language. Yet, this unity is not ultimately determined by extralinguistic contents, like ideas in the case of ideograms or the shape of objects for pictograms. For it is always the alphabetic regime which orients, through the typewriting grid guiding the gestures, the articulatory principles of the resulting symbols. But where do the monogrammatic figures get their formal unity from then? Here lies one of the major originalities of the gesture keyboards, namely the importance of the repetition in the establishment and the evolution of the system. Indeed, as long as each monogram depends for its construction on the letters it is composed, the unity of these figures is kept on hold, as just one possibility among so many other random paths through the keys of a keyboard. But as we have seen, as soon as the same path is performed a sufficient number of times, a gradual transition can be expected from a path punctuated by the characters to independent unified traces of continuous gestures. This way, the written expression of words, as autonomous units, is directly correlated to the probabilities of words in language. Writing does not merely represent linguistic units, but actively contributes to their identification.

12

28

Swipe

Among the series of new scriptural forms associated with the emergence of the digital, there is one which, from this viewpoint, deserves special attention: gesture keyboard entry, more commonly known as “Swipe”. The term swipe refers to all the operations which imply sliding a finger on the surface of the touch screen of a digital device. In the context of text entry, it refers to a writing technique that allows users of digital devices to write the words of the intended text not by typing each letter — a practice inherited from mechanical keyboards —, but by sliding the finger through the different corresponding keys. So, to write the word unavoidable, one places the finger on the keyboard’s zone corresponding to the letter u , then successively slides it through the letters n, a, v and so on, until the last, e, without losing contact with the screen’s surface. Introduced originally in 2003 by Per-Ola Kristensson in collaboration with Shumin Zhai (2003) – one student at Linköping University (Sweden), the other researcher at IBM [3] – gesture keyboard entry was included in many different applications that shipped with touch screen tablets and smartphones. Since then, it has been adopted by the primary companies developing operating systems for laptops, like Apple, Google, or Microsoft who integrated these systems as a native feature. The development of this technology was motivated by the need for digital devices to respond to the demand for speed and ergonomics required by handwriting practices. The empirical studies showed that this new writing method allowed an average increase of 30% in speed over typewriting on touch-screen [4]. The simplicity of the method, at least when one is already familiarized with the keyboard layout, provides a virtually flat learning curve. Also, the usage of this technique significantly reduces typing errors. All these characteristics, focusing on the method’s efficiency, provide a purely technical image of the purpose of gesture keyboards. However, upon closer inspection, the interest of this form of writing cannot be reduced to a strictly technical advantages as a user interface.

14

26

Indeed, the last decades have witnessed a profusion of expressive means in digital writing practices, which transgress in every way the limits supposedly imposed by the typing interface of portable devices: emojis, gifs, photos, videos, memes, drawings, screen captures, hypertextual links, maps, sketches, annotations, voice recordings... All these scriptural practices constitute a variety of openings for digital textuality whose source lies in the typewriting’s incapacity to satisfy the needs and principles of everyday spontaneous writing — such as expressivity, figurality, speed or evanescence — monopolized until recently by handwriting. Paradoxically, the moment typescript began the total and unequivocal conquest of writing during the digital revolution, writing found itself more than ever freed from all the constraints that keys, gears, sticks, springs, joints and lead types had placed upon it. From this perspective, this moment is comparable to the one following the emergence of photography a century and a half ago. But not according to the sense media-theoretical perspective could project upon this event, namely the continuation of painting by other means, and the consequential capture of the image in new conditions and constraints at odds with the sense of the pictorial medium, forced henceforth to fight against its own obsolescence. We should rather think here about the period – situated by Michel Foucault between the years 1860 and 1880 (Foucault, 2001) – when the unregulated intertwinements of pictorial and photographic practices led to a frenetic circulation of images, a true carnival for the eyes. A period in which, if only during the blink of an eye, the image was liberated from media constraints as it suddenly became plural. This moment was liberating for the image as much as it was for painting: far from being substituted, displaced or subjected to the needs of the new photographic medium, painting released itself from the injunctions of representation, which it had assumed as its own nature for centuries. The same is true of textuality under the influence of the digital. Indeed, the last two decades have been celebrating the Saturnalia of writing. Emojis, gifs and memes are certainly the most spectacular expression of this phenomenon. Through the image, they introduce a kind of spatiality and dynamism which are generally and by principle absent in typewriting.

16

Part C. essay by Gianni Gastaldi & Bérénice Serra

18

22

20

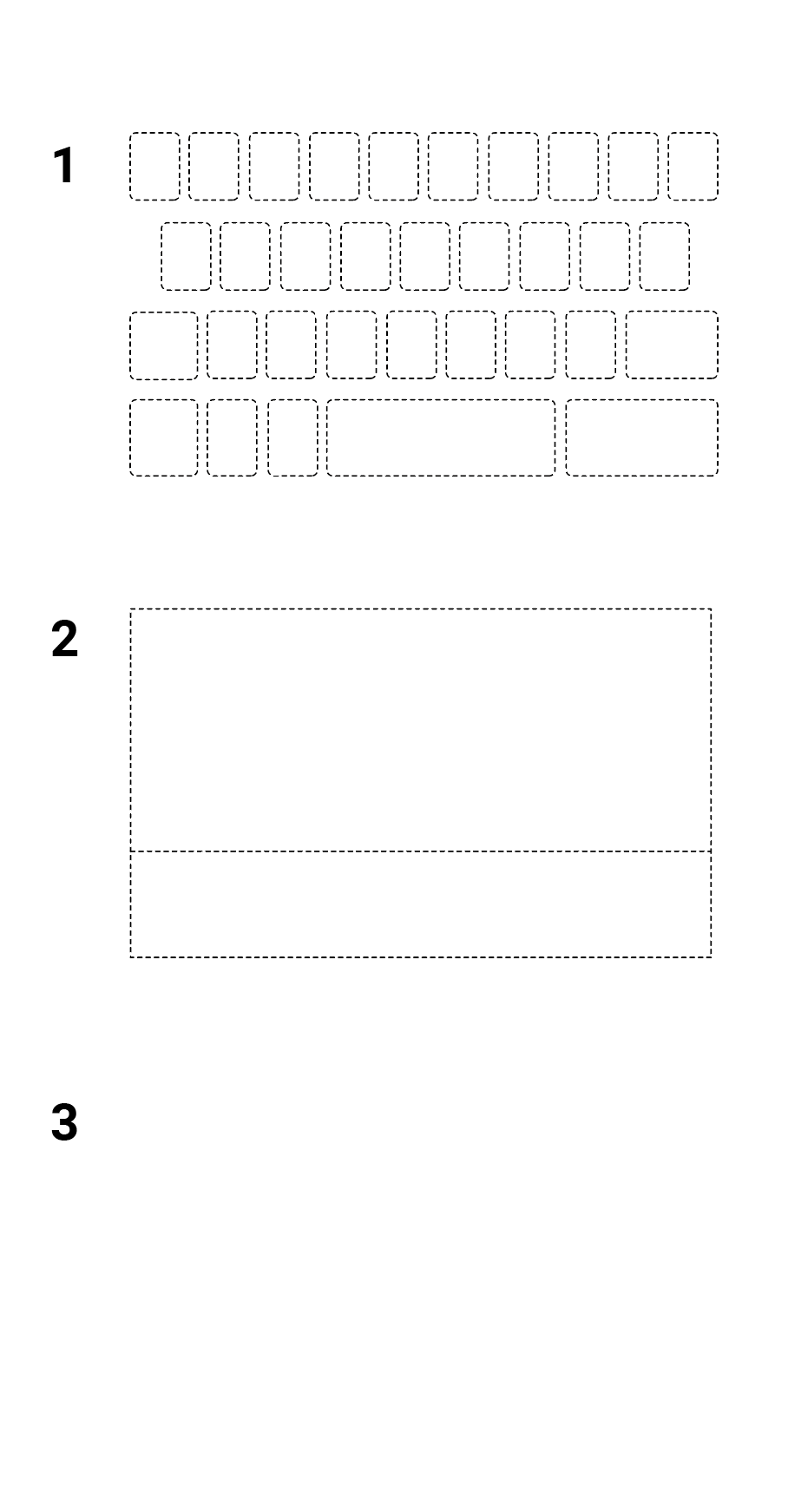

Nota bene

This publication was made in a web browser with free and standard tools such as HTML and CSS. You can print your own copy from the page http://berenice-serra.com/swipe, using Google Chrome or Chromium browsers. As the printed version relies on the online one, the contents could be modified or updated at any time. contact: hello@bereniceserra.com

2 — 9

Part A. three principles of swipe writing

10 — 23

Part B.three writing exercices

24 — 38

Part C.essay by Bérénice Serra & Gianni Gastaldi

41

Nota bene

39

5

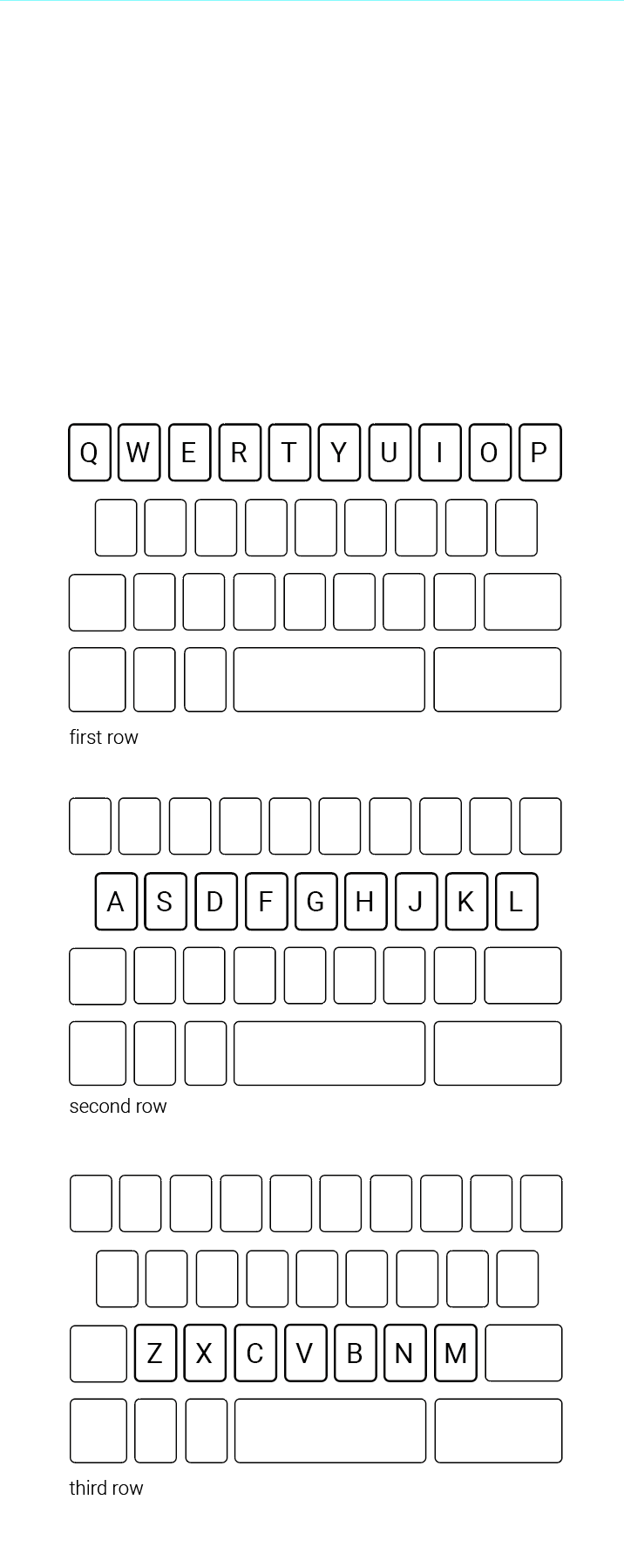

This writing system requires to memorize the position of the letters on the keyboard.

35

Towards a naturality of digital writing

Stratified organization, oppositional identification, evolutive performance – these are the

principles that emerge from a digital writing practice like gesture keyboard entry when, as

with Swipe, it is taken seriously as a writing practice

tout court. These principles

are not specific properties of

a medium or a technology. They command the being of

any writing where

the writing of a natural language is concerned. Yet, if all writing is subject to these general

laws of language, a writing system like the one suggested by Swipe integrates them, so to speak,

by design. Not that they constitute features of a software that would make it more effective than

others, therefore more attractive to potential buyers. Nor do these properties consciously guide its

design in the minds of its creators. Incidentally, identifying a single creator of this type of

system has more to do with a founding myth than with historical conditions, since the emergence of

these ideas takes place at the crossroads of a multiplicity of practices and reflections difficult

to locate. Design is therefore only anecdotal here. Swipe integrates these principles by system, so

to speak. This means that, as a system and independently of the original designs, knowing how to manipulate

it implies,

if not becoming aware of, at least problematizing the principles that silently govern all writing.

Performing Swipe beyond the limits imposed by the interface of digital devices is to perform the writing of language in its most natural form.

Finally, the perspective thus offered by Swipe on writing in the digital age offers clues about the

characterization of the digital as such. Since before becoming a phenomenon related to technology, science

or society, what is called nowadays "digital" concerns the nature and the experience of textuality itself.

A study of this question remains undoubtedly to be carried out, and falls out of the scope of these pages.

But let us say at least this: at the origin of what we call digital there is the idea, both simple and radically new,

that the purpose of a text is not, or not only, to be read, but to be performed or executed. Or more precisely,

drawing from the lexicon of programming languages, to bee run.

An expression like sum([1,2,3]),

as a proper piece of digital textuality, i.e. as a code,

does not ask so much to be read as to be transformed into another, namely 6

, to which it is already equivalent in some sense.

7

When the letters of a word are connected, the word appears as a monogram.

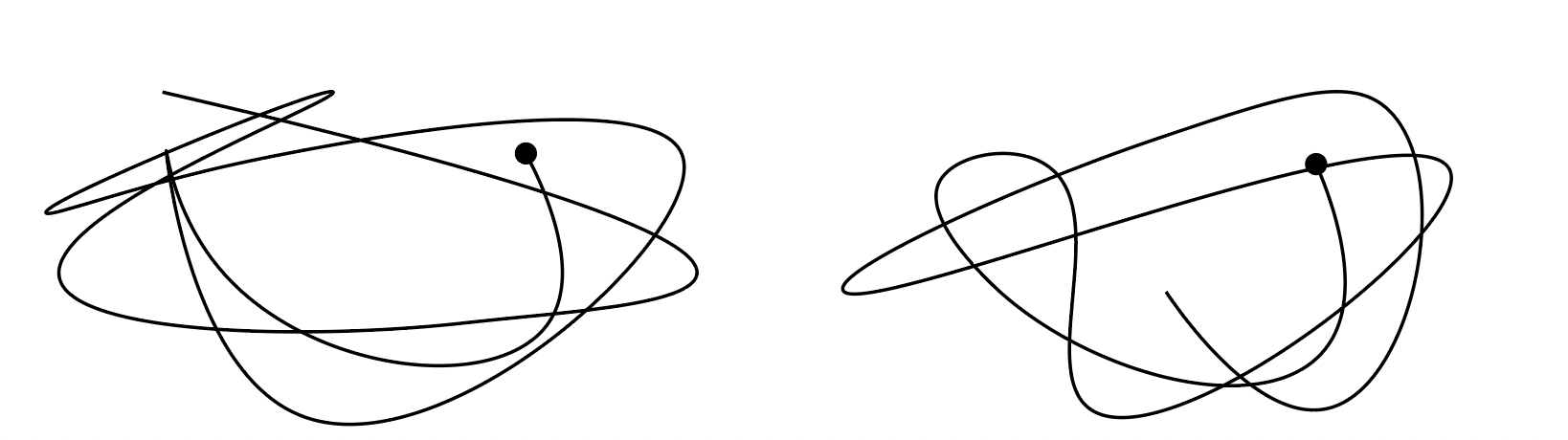

33

Performance and change

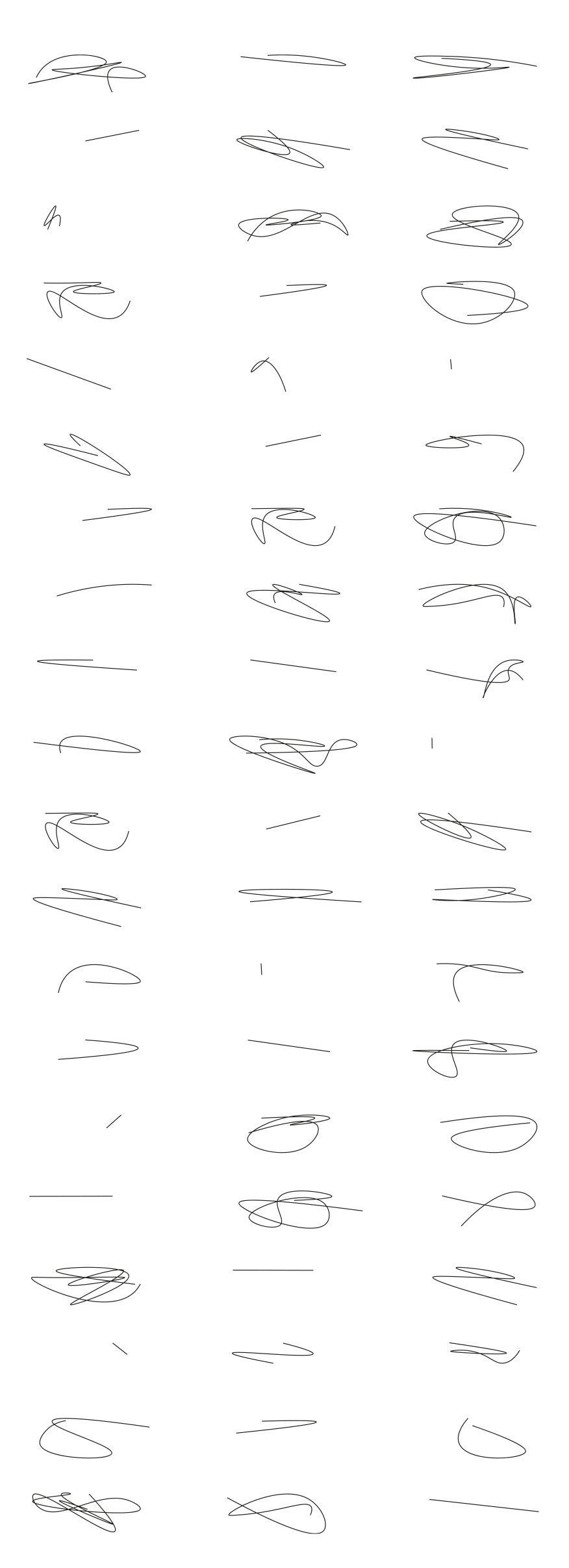

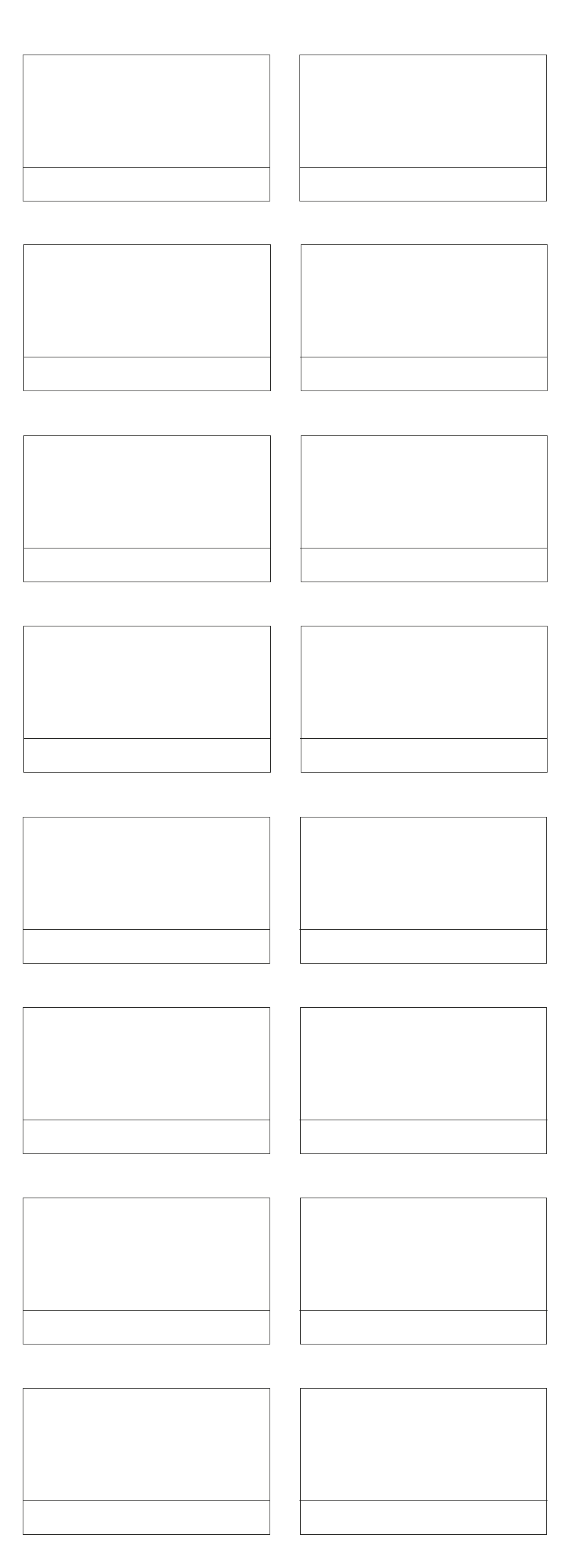

There is, however, one point where this reduction of possibilities to a pre-existing vocabulary may

raise doubts. For like the word, the idea of a finite list of terms is no less an artifact. Thus, adopting

such an artifact as a fundamental constraint on everything that can be written in a language risks having

highly constraining effects on the creative power of any language. This can be easily observed by trying to

write an out-of-vocabulary word, such as undecoratable.

In its current state, the algorithm will invariably render the word undercoating instead, whose

corresponding pattern is, among those of the vocabulary, the closest to the pattern produced by

the path of undecoratable (Fig.2). A system constructed in

this way then risks embodying a deeply conservative conception of writing, neglecting any originality by the irrevocable

restitution of a pre-established coherence. The spelling correction mentioned above could be understood as nothing more

than a manifestation of this conservatism. This phenomenon is all the more flagrant as one moves away, voluntarily or

not, from the current uses of the language, going as far as the extreme case where the algorithm keeps finding a "correct"

word even when the path on the touchscreen is deliberately chaotic.

In the various implementations of gesture keyboards, this difficulty is circumvented by resorting to typewriting, which

is always possible on the virtual keyboard of digital devices. If we consider gesture keyboard entry as a writing system

in its own right, it suggests that such a system cannot be self-sufficient, since typewriting would then remain the writing’s

norm and its ultimate guarantee. But on closer examination, this limitation doesn’t come from an intrinsic weakness of the

principles on which it is based and is therefore only apparently necessary. For if the list of words constituting the vocabulary

is necessarily finite, it does not need to be closed. Indeed, its closed character results from an arbitrary decision. But

nothing stops us from making the content of this list dynamic, so that elements could constantly be added or removed as writing

habits evolve. Even more, it is the fundamental principle of gesture keyboard entry that invites it, based, as we have seen, on

the ability to grant a simple and separate existence to frequent gestures initially composed of pre-existing units (typically characters).

Figure 2. Patterns for undecoratable (left) and undercoating (right).

Figure 2. Patterns for undecoratable (left) and undercoating (right).

9

Recurring character sequences such as "able" or "yourewelcome" define a repertory of usual forms.

31

Or even to their construction. For the very logic of this system suggests that sticking here to words is after all only an arbitrary choice. For it is not only lexical units that respond to this mechanism. The frequency of supra-lexical expressions such as for sure, right now, excuse me, not yet, thanks a lot, what’s up, I don't know, do it yourself, in my opinion, and many others, is enough to justify their existence as linguistic units in their own right, in a way that a writing system like Swipe would naturally express. And the same is true of sub-lexical units. Words like inextricable or unfathomable are certainly not among the most frequent in the English language. Yet the sequence able (just like tion , ment or ness, for instance), is among the most probable four-letter sequences, and as such, the corresponding trace on Swipe is likely to step out as an independent or at least perfectly distinct unit. As such, Swipe has a singular critical power towards the nature of language. For in fact, as has often been pointed out by linguists, the word does not exist. The logic no less than the practice of this writing system thwarts the privilege traditionally granted to the word in the writing of language. And, in exchange, this system reveals a more complex organization of language, whose unexpected and radical originality is to have the power to grasp morphological, syntactic, and even stylistic stratification and articulation principles at the level of the writing itself.

Identity in difference

From their very first attempts, new users systematically notice with surprise the remarkable efficiency of gesture keyboards as implemented in everyday digital devices. Indeed, the accuracy in the rendering of the intended words can certainly be unexpected, considering the highly imprecise and variable paths on the screen. The device gets its efficiency from the way the recognition of the figures is performed. Against the most basic intuition of what the underlying mechanism must be, the sequence of letters finally resulting from a given path is not the direct consequence of the swiped keys. As an immediate proof, just try to swipe a mechanical keyboard [7].

29

For ultimately, nothing prevents us from considering the Swipe method as a writing system in its own right. Setting aside the properties of digital interfaces, the system involved in gesture keyboard entry could be used throughout a variety of heterogenous media: ink on paper, chalk on blackboard or tag on a wall, no less than smartphones or tablets. Thus detached from the different media, this writing system could exhibit its own consistency at the fortunate crossroads of the discontinuous typing imposed by typewriters and the smooth gestuality of cursive script. The mere consideration of this possibility allows the evaluation of the conceptual effects this new practice of textuality could generate over the nature of writing and its relation to language. The key to this possibility lies in a mechanism that early research already considered as one of the driving principles of this approach, namely the dynamic transition from typing to gestures. Indeed, the system behind this method wants this transition to occur naturally, controlled by the frequency at which the different words are typed. If at first, to enter a word, one has to go through the letters one by one, the repeated entry of the same word eventually sets the gesture free from the control of the letters on the keyboard, investing it with a new unity and independence. In this transition, a repertoire of simple gestures is progressively built by the user, like units in an extended vocabulary he or she can then use to bypass traditional alphabetical entry. Yet, these units remain purely gestural only because their trace on the screen is ignored. It is enough to collect these traces for the premises of a real writing to be brought to light. This is what proposes the artwork Swipe, presented in the graphic booklet preceding this text [5]. Thus, gestures become forms, as they extract an implicit figural dimension from typewriting, capable to constitute an autonomous writing system. The forms extracted from gestures freed from the typewriting grid constitute true monograms, as the letters intertwine to form a single character. However, these monograms are of a radically new kind because, while each one reaches an autonomous existence, their purpose is not to constitute themselves as independent signs, like icons or logos.

13

27

New gifs and memes are constantly being created and the list of emojis is growing year after year, while type forms, generated by type machines, keyboards, or platforms such as ASCII or Unicode, haven’t been designed to evolve. But those are not the only manifestations. Textual inventions blossom everywhere, connecting simple sparkles of individual ingenuity to powerful collective manifestations, like the ones behind hashtags or inclusive writing. Crossing the alphabetic principle to and fro by a myriad of smileys, ‘at’ symbols and stunned John Travoltas, digital textuality reminds us, in its joyful anarchy, that writing has never been and could never be the sober recording of a sequence of characters. However, if these scriptural practices allow us to remember what writing is not, they are not sufficient to tell us what it actually is. Moreover, the radical openness of digital textuality poses a constant risk of dissolving writing through the alleged immediacy of image or speech. The presumed liberation from typing constraints awakens the old ghosts of transparency, which would only like to see in writing the sterile copy of sight and speech. While emojis and memes, for instance, comprise quite original articulations between textuality and image, other forms circulating in this same space of textuality, such as photographs or sound recordings when they are not accompanied by other forms of textuality, or when they are only based on vocal or image recognition, could push to think that writing is only a redundant and obsolete medium, thus doomed to disappear. But textuality is irreducible to image or sound, even when sound and image are recorded, even when at times textuality relies on or lets itself be continued by them. Faced with this tendency towards illiteracy within digital practices, we should remember one simple yet significant fact: no digital device can nowadays fully use its computational power without a keyboard. Neither can we imagine how it could without pushing the users into a position of extreme passivity. To such an extent that the persistence of keyboards, and even their central position in digital devices, must be taken as a symptom of the fact that, although writing is not the same as lining up letters, writing does constitute a certain work on characters. Thus, to grasp the positive aspects the new textual practices in the digital context bring forward concerning the nature of writing, we must focus on how these practices can invest the principles of alphabetical writing with new powers.

15

Swipe, or writing tout court

The Saturnalia of digital textuality

The widespread use of digital devices generated countless transformations in writing practices. One of them, although discrete, was decisive in every way: the adoption of typewriting as the primary choice for longhand. First as a possibility, then as something desirable, eventually unavoidable, the miniaturization of computers turned the latter [1] into the privileged go-between for individuals and their worlds, among a great variety of societies across the planet [2]. Hence, for better or for worse, QWERTY typewriting keyboards, or their corresponding counterparts in different linguistic areas, constitute the primary interface between digital devices’ operational principles and the practice of natural language by their users. To such an extent that writing with a keyboard outran handwriting, which until recently held the monopoly of spontaneity over natural language writing. Yet, we would be wrong to think that typewriting is replacing handwriting like the artificial can replace the natural. We should rather consider, as typewriting is spreading to a point of naturalization, that it is becoming a new form of handwriting. This observation could lead to another consideration regarding the incidence of material recording media on the production of meaning, and more generally, of the media specific to the digital era. The reader would then risk facing, among other things, another glorification of typewriters as technical substitutes for thought. But computers, insofar as they are calculating or computational devices, inherited from type machines little more than their carcasses. Typewriters may be recording devices of natural language thereby affecting the underpinnings of thought, nonetheless the majority of today’s literate population do not carry typewriters in their pockets for that reason. Looking closely, the assimilation of typewriting practices resulting from digital developments rather reveals that writing cannot be reduced to the material conditions of its recording, thus indicating how this development transforms before our eyes the connections between writing and language. If one thing has become evident since typing widespread as a proper handwriting, it is not so much the way textuality allows itself to be informed by (or even enclosed in) the surface of the keyboard, but the multiple means it has in its daily practice of escaping it.

17

23

19

21